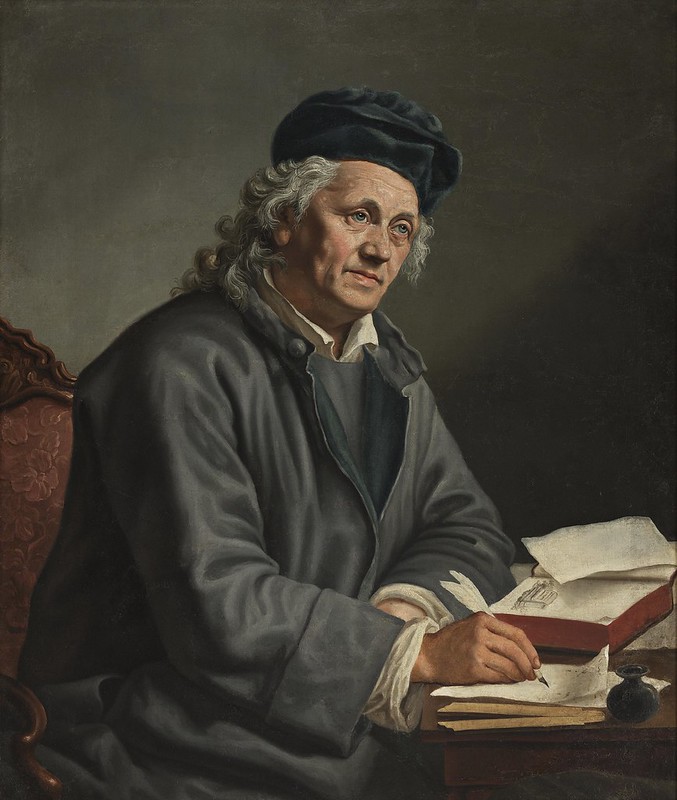

Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721-1783)

- Concerto (c-moll) per il Cembalo Obligato (c.1770)

previously attributed to Johann Sebastian Bach

Performers: Luciano Sgrіzzі (1910-1994, cembalo); Orchestre Jean-François Pаllаrd

Painting: Christoph Friedrich Reinhold Lisiewski (1725-1794) - Portrait of Johann Philipp Kirnberger

Further info: Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721-1783) - Flotensonaten

---

German theorist and composer. All information relating to his career

before 1754 is based on F.W. Marpurg’s biographical sketch (1754), an

autograph album described by Max Seiffert (1889) and comments found in

letters Kirnberger wrote to J.N. Forkel in the late 1770s. He received

his earliest training on the violin and harpsichord at home, and

attended grammar school in Coburg and possibly Gotha. He studied the

organ with J.P. Kellner in Gräfenroda before 1738, and then the violin

with a musician named Meil and the organ with Heinrich Nikolaus Gerber

in Sondershausen in 1738. According to Marpurg, Kirnberger went in 1739

to Leipzig, where he studied composition and performance with Bach for

two years (the autograph book shows that he was in Sondershausen in 1740

and Leipzig in 1741, which does not preclude his period of study with

Bach). In June 1741 Kirnberger travelled to Poland, where he spent the

next ten years in the service of various Polish noblemen. He also held a

position as music director at the Benedictine convent at

Reusch-Lemberg. In 1751 Kirnberger returned to Germany apparently

stopping at Coburg and Gotha before going to Dresden, where he studied

the violin for a short time. He was then engaged by the Prussian royal

chapel in Berlin as a violinist. By 1754 he had resigned that post and

obtained permission to join the chapel of Prince Heinrich of Prussia,

and in 1758 was given leave to enter the service of Princess Anna Amalia

of Prussia, a position he retained to the end of his life. Kirnberger

was among the most significant of a remarkable group of theorists,

centred in Berlin, which included J.J. Quantz, C.P.E. Bach and Marpurg.

Almost without exception his contemporaries described him as emotional

and ill-tempered, but dedicated to the highest musical standards.

Criticized for being inflexible, conservative, tactless, and even

pedantic, his detractors still acknowledged his devotion to his students

and friends. These included his employer Princess Anna Amalia (whose

famous library he helped to assemble), and such eminent musicians as

C.P.E. Bach, J.F. Agricola, the Graun brothers, J.A.P. Schulz (his most

important pupil) and the encyclopedist J.G. Sulzer, to whose Allgemeine

Theorie der schönen Künste (1771-74) he contributed articles. Most

accounts agree that he was a middling performer and that his

compositions were correct if uninspired. Many are in a galant style

similar to that of C.P.E. Bach; others are in the older ‘strict’ style

in the manner of J.S. Bach, but in neither category does Kirnberger

display the harmonic or melodic imagination of his models. Although his

musical knowledge was wide and profound, it was, according to his

contemporaries, disorganized. He found it so difficult to express his

ideas in writing that he had to call on others to edit or even rewrite

his theoretical works (Die wahren Grundsätze (1773), for example, was

written by J.A.P. Schulz under Kirnberger’s supervision). Nonetheless,

even his most severe critics, such as Marpurg, considered his

theoretical and didactic works to be invaluable. Kirnberger regarded

J.S. Bach as the supreme composer, performer and teacher. He regretted

that Bach left no didactic or theoretical works and tried through his

own teaching and writing to propagate ‘Bach’s method’. His devotion to

this cause is reflected in 14 years’ intermittent effort to obtain the

publication of all Bach’s four-part chorale settings.

Cap comentari:

Publica un comentari a l'entrada